Harnessing black metal to boost solar power generation

Researchers have engineered a solar thermoelectric generator 15 times more efficient than current state-of-the-art devices.

In the quest for energy independence, researchers have studied solar thermoelectric generators (STEGs) as a promising source of solar electricity generation. Unlike the photovoltaics currently used in most solar panels, STEGs can harness all kinds of thermal energy in addition to sunlight. The simple devices have hot and cold sides with semiconductor materials in between, and the difference in temperature between the sides generates electricity through a physical phenomenon known as the Seebeck effect.

But current STEGs have major efficiency limitations preventing them from being more widely adopted as a practical form of energy production. Right now, most solar thermoelectric generators convert less than 1% of sunlight into electricity, compared to roughly 20% for residential solar panel systems.

That gap in efficiency was dramatically reduced through new techniques developed by researchers at the University of Rochester’s Institute of Optics. In a study published in Light: Science and Applications, the team described their unique spectral engineering and thermal management methods to create a STEG device that generates 15 times more power than previous devices.

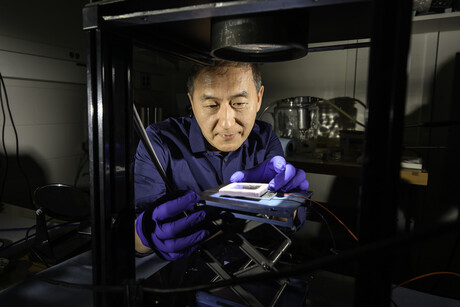

“For decades, the research community has been focusing on improving the semiconductor materials used in STEGs and has made modest gains in overall efficiency,” said Chunlei Guo, a professor of optics and physics, and a senior scientist at Rochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics. “In this study, we don’t even touch the semiconductor materials — instead, we focused on the hot and the cold sides of the device instead. By combining better solar energy absorption and heat trapping at the hot side with better heat dissipation at the cold side, we made an astonishing improvement in efficiency.”

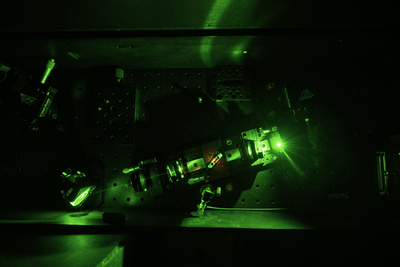

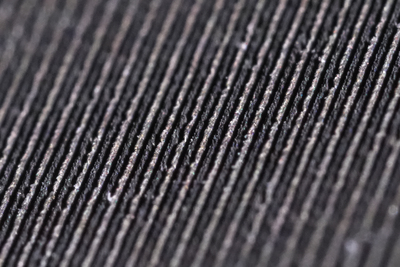

The new, high-efficiency STEGs were engineered with three strategies. First, on the hot side of the STEG, the researchers used a special black metal technology developed in Guo’s lab to transform regular tungsten to selectively absorb light at the solar wavelengths. Using powerful femtosecond laser pulses to etch metal surfaces with nanoscale structures, they enhanced the material’s energy absorption from sunlight, while also reducing heat dissipation at other wavelengths.

Second, the researchers “covered the black metal with a piece of plastic to make a mini greenhouse, just like on a farm”, Guo said. “You can minimise the convection and conduction to trap more heat, increasing the temperature on the hot side.”

Lastly, on the cold side of the STEG, they once again used femtosecond laser pulses, but this time on regular aluminium, to create a heat sink with tiny structures that improved the heat dissipation through both radiation and convection. That process doubles the cooling performance of a typical aluminium heat dissipater.

In the study, Guo and his research team provided a simple demonstration of how their STEGS can be used to power LEDs much more effectively than the current methods. Guo says the technology could also be used to power wireless sensors for the Internet of Things, fuel wearable devices, or serve as off-grid renewable energy systems in rural areas.

Molecular Velcro coating boosts solar cell efficiency

Researchers have developed a new coating layer that enhances the durability and efficiency of...

Predictive AI model enhances solid-state battery design

ECU researchers are working on ways to make solid-state batteries more reliable with the help of...

Boosting performance of aqueous zinc–iodine batteries

Engineers from the University of Adelaide have enhanced aqueous zinc–iodine batteries using...