Chip-scale magnetometer for high-precision magnetic sensing

Researchers have developed a precision magnetometer based on a special material that changes optical properties in response to a magnetic field. The device, which is integrated onto a chip, could benefit space missions, navigation and biomedical applications.

High-precision magnetometers are used to measure the strength and direction of magnetic fields for various applications. However, many of today’s magnetometers must operate at extremely low temperatures — close to 0 kelvin — or require relatively large and heavy apparatus, which restricts their practicality.

“Our device operates at room temperature and can be fully integrated onto a chip,” said Paolo Pintus from the University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB) and the University of Cagliari, Italy, co-principal investigator for the study. “The light weight and low power consumption of this magnetometer make it ideal for use on small satellites, where it could enable studies of the magnetic areas around planets or aid in characterising foreign metallic objects in space.”

In Optica, the research team, led by Galan Moody of UCSB, with Caroline A. Ross of MIT also serving as a co-principal investigator, describe their new magnetometer. They show that the device can achieve a sensitivity comparable to that of other high-performance, but less practical, magnetometers.

“The magnetometer could be useful for magnetic navigation, providing an alternative navigation source in environments where GPS is jammed, spoofed or unavailable such as underwater, in tunnels or during electronic warfare,” Pintus said. “It could also benefit medical imaging methods such as magnetocardiography and magnetoencephalography, which currently depend on highly sensitive magnetometers that require bulky, costly equipment.”

Turning light into magnetic insight

The new magnetometer was developed as part of the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Quantum Sensing Challenges for Transformational Advances in Quantum Systems program. It builds on previous works in which the researchers used magneto-optic materials to develop a magneto-optic modulator and integrated magneto-optic memories for photonic in-memory computing.

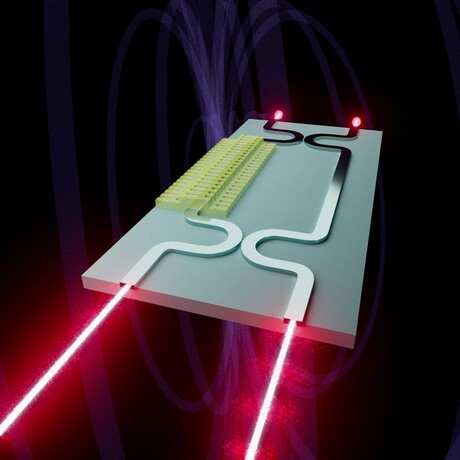

For the new device, the researchers used a magneto-optical material called cerium-doped yttrium iron garnet (Ce:YIG), which was provided by Yuya Shoji from the Institute of Science Tokyo. When an external magnetic field is present, light propagating through Ce:YIG experiences a phase shift that can be detected with an optical interferometer.

Optical interferometers work by splitting light into two paths and then recombining those paths. By placing the magneto-optic material in one of the paths, the researchers were able to measure whether the light in that path becomes brighter or dimmer, which was then used to determine the strength of the magnetic field.

To make the magnetometer practical, the researchers built it on silicon photonics, a technology that creates tiny optical devices using the same silicon found in microchips. This allowed them to create a device with minimal size, weight and power consumption that can be integrated with other chip-based optical components such as lasers and photodetectors.

“Historically, magneto-optic materials have been used almost exclusively in optical isolators and circulators, a specialised class of devices that enforce unidirectional light propagation,” Pintus said. “By incorporating magneto-optic materials directly onto a photonic integrated circuit, we expand the range of integrated photonic components and introduce functionalities that stem from their unique properties.”

The magnetometer operates with ordinary laser light, but the authors have shown that injecting quantum light can improve its performance. “The idea is similar to what’s already done in large optical interferometers used to detect gravitational waves, like LIGO,” Pintus said. “By using squeezed light — a special quantum state of light — we can reduce noise and increase the instrument’s sensitivity.”

High sensitivity from a small device

Using a combination of multi-physics simulations and experimental measurements, the researchers showed that the device can detect magnetic fields ranging from a few tens of picotesla to 4 millitesla. For comparison, Earth’s magnetic field is about 100,000 times stronger than the minimum detectable field, yet around 1000 times weaker than the maximum field the instrument can measure. This sensitivity matches that of high-performance cryogenic magnetometers, without their restrictive temperature, size, weight or power constraints.

Now that the researchers have taken an important step towards demonstrating the feasibility of their approach, they are working to improve performance by exploring alternative magneto-optic materials and integrating quantum elements for even greater sensitivity. They note that transitioning the research into a commercial product would require the challenging task of creating a fully integrated chip-based system that includes other key components, such as an integrated laser and photodetector.

Turning RFID tags into scalable passive sensors

Researchers from UC San Diego have used low-cost RFID tags to develop analog passive sensors that...

Smart buoy tech live streams data 24/7 from sea floor

A Perth-based company has developed the Nodestream protocol, a bespoke solution that uses...

Engineers discover a new way to control atomic nuclei as “qubits”

Using lasers, researchers can directly control a property of nuclei called spin, that can encode...