Turning waste wood into biodegradable PCBs

Modern printed circuit boards are made from petroleum-based materials and are difficult to recycle. Empa researchers have developed a biodegradable version — an important step towards sustainable electronics. Their biomaterial is based entirely on wood and can be processed into functional circuit boards for electronic devices.

They are the ‘heart’ of every electronic device, from laptops to electric toothbrushes: printed circuit boards, also known as PCBs. These rigid boards are covered with copper traces and soldered electronic components and are usually a tell-tale green colour. They are, however, not exactly environmentally friendly.

The substrate generally used for the traces and components is a laminate made of fibre-reinforced epoxy resin. This composite material is based on petroleum and cannot be recycled. Proper disposal is costly, for example in a special pyrolysis furnace with exhaust air purification — a challenge, given the large quantities of discarded circuit boards that accumulate for disposal each year.

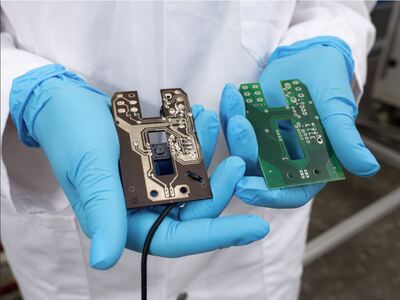

Researchers led by Thomas Geiger from Empa’s Cellulose and Wood Materials laboratory are working on a ‘green’, ie, sustainable, option — which is actually brown. As part of the EU research project HyPELignum, they developed a wood-based substrate for PCBs that can compete with conventional epoxy resin — and is also completely biodegradable. The researchers have incorporated the boards made from this material into functioning computer mice.

Dream team of fibrils and lignin

The source for the carrier material is a natural mixture of cellulose with a small amount of lignin. Strictly speaking, it is a waste product. “Our partners at the TNO research institute in the Netherlands have developed a process for extracting the raw materials lignin and hemicellulose from wood,” Geiger said. “What remains is brownish lignocellulose, for which there has been no use so far.” Geiger, who has a long track record of research into electronics made from cellulose, saw the potential of the raw material.

In order for the flaky lignocellulose to become a high-tech product such as a PCB, it must first be ground by adding water to break down the relatively thick cellulose fibres into thinner fibrils. This creates a fine network of slender fibrils that are interconnected. In a next step, the water is squeezed out of the mixture under high pressure. The fibrils move closer together and dry to form a solid mass. The researchers call this process hornification. “The lignin contained in the material serves as an additional binding agent,” Geiger said.

The resulting hornified board is almost as resistant as a conventional circuit board made of fibre-reinforced epoxy. This is because the compostable board is still sensitive to water and high humidity. But water is needed because, “if no water can penetrate the carrier material at all, microorganisms such as fungi can no longer grow in it — and it would thus not be biodegradable”, Geiger said.

A compostable computer mouse

Nevertheless, the researchers are confident that the resistance of lignocellulose-based biomaterials can be further improved with suitable processing methods. “For certain applications, however, we also need to rethink our relationship with electronics. Many electronic devices are only in use for a few years before they become obsolete — so it doesn’t make sense to manufacture them from materials that can last for hundreds of years,” Geiger said.

The researchers have printed conductive traces on their sustainable circuit boards and fitted them with components to produce functioning electronic devices, such as a computer mouse or an RFID card. At the end of its service life, such a device could be composted given the right conditions. Once the carrier material has decomposed, the metallic and electronic components can be removed from the compost and recycled.

Next, the researchers want to make their biomaterial for circuit boards more resistant without compromising its biodegradability. The project partners also plan to produce further demonstration devices with lignocellulose plates at the end of the HyPELignum project in 2026. Transfer to industry is also a must: “Together with Swiss and European companies, we want to develop further applications for the lignocellulose material,” Geiger said.

Next-gen polymer IR lens technology for thermal imaging

Flinders University researchers have developed a sustainable, repairable and recyclable polymer...

Quantum-inspired wireless tech to boost 6G performance

Researchers have developed a quantum-inspired method for optical wireless communication, to...

Internal quantum batteries to power scalable quantum CPUs

A new quantum-battery‑powered architecture, developed by researchers from CSIRO and the...