So, who’s doing what with graphene?

Friday, 08 March, 2013

From super-fast electronics to detecting illicit drugs and finding viruses in humans - these are some of the promises of a new substance that has scientists worldwide super excited. The substance is graphene and it is poised to become the wonder material of the 21st century if intense research activity on many fronts comes up to expectations and creates a whole new generation of products.

Australia has not been left out of the action either as it is making a major contribution to unravelling its mysteries. Scientists at the CSIRO and the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology say they have discovered a way to make high-speed electronics possible using graphene.

However, the material is not giving up its secrets without a struggle: so a $92m research institute is to be built at the University of Manchester in Britain where the material was first identified in 2004. This National Graphene Institute of 7600 m² will have two ‘clean rooms’. There will also be a 1500 m² research laboratory where scientists can collaborate with their colleagues from industry and other British universities. The institute is due to be completed by 2015.

Funding for this significant investment comes from a $57m grant from the British government and the university has applied for $35m from the European Research and Development Fund.

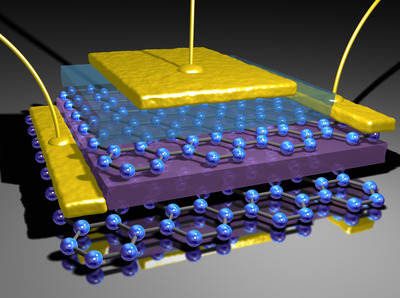

Cambridge University will look into flexible graphene and its use in optoelectronics, which may include touch screens and other display devices under an $18m grant. In London, Imperial College will use $7m to investigate aerospace applications while working with industrial companies such as Airbus. Durham, Exeter and Royal Holloway universities are also involved in graphene research. They, too, are working with companies such as Dyson, Rolls-Royce, Sharp, Philips and Nokia. If Nokia is successful in developing the material, it may be possible, says the company, to build mobile phones that are very light, durable and less susceptible to overheating.

A major focus of the research at Royal Holloway will be on developing epitaxial graphene, which could well succeed silicon. The material will be tested at terahertz frequencies, which could lead to more detailed deep space observations, the ability to detect explosives and drugs, and to health screening to produce detailed images of blood vessels.

With such serious money going into research, just what is this substance called graphene that is getting so many scientists so excited?

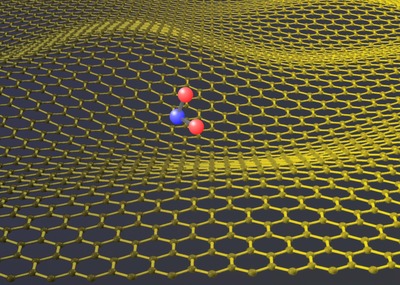

Discovered in 2004 at Manchester University, graphene is a two-dimensional material of a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb or chicken wire structure. It is the thinnest yet strongest material known and conducts electricity as well as copper and outperforms all other materials as a conductor of heat. It is transparent but so dense that even the smallest helium atom cannot penetrate it. It is also the hardest material known and 300 times stronger than steel.

When it was first discovered, its free state was considered to be unstable but this was quickly disproved once it was isolated in 2003.

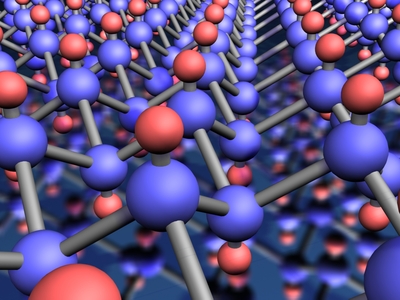

Meanwhile, CSIRO and RMIT researchers in Australia have developed a process called ‘exfoliation’, in which layers 11 nm thick have been created to produce conductive nanomaterial comprising layers of crystal called molybdenum oxides. This arrangement is said to encourage a free flow of electronics at ultrahigh speeds.

Dr Serge Zhviykov, of the CSIRO, says that atomic-scale ‘road blocks’ in conventional materials obstruct electrons and scatter them as they pass through. But layered sheets of the nanomaterial allow electrons to pass through at high speed with ‘minimal scattering’.

“This means we can build devices that are smaller and transfer data at much higher speeds,” he says.

Collaboration on the project also came from Monash University, the University of California, Los Angeles and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Details of this research have been published in a paper: ‘Enhanced Charge Carrier Mobility in Two-Dimensional High Dielectric Molybdenum Oxide’.

A curiosity of graphene is that if layers of it are stacked one on top of another, they form graphite, a common enough substance found in every lead pencil. In fact, anyone who has ever drawn a pencil line has probably made graphene.

However, the last word should go to Nokia, whose research centre scientist Jani Kivioja says:

“When we talk about graphene, we’ve reached a tipping point. We’re now looking at the beginning of a graphene revolution. Before, we figured out a way to make cheap iron that led to the industrial revolution. Then there was silicon. Now it’s time for graphene.”

Light-powered optical modules boost AI efficiency

Researchers have developed a new generation of AI hardware that runs on light instead of...

New materials could boost the energy efficiency of microelectronics

By stacking multiple active components based on new materials on the back end of a computer chip,...

Diamond sensor reveals hidden magnetic fluctuations

Scientists have used entangled defects in diamonds to detect magnetic signals at record...